- Born 1892, died 1967

- Guild member 1920-1967

- Stone Carver

Table of Contents

Life

The following is an essay by Joe Cribb (grandson) entitled Joseph Cribb (1892-1967) and included in the book Eric Gill and Ditchling: The workshop tradition (ISBN 0-9516224-9-8), reproduced with permission. Joe Cribb continues to assert his rights under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

Joseph Cribb had grown up in an Arts & Crafts community centred around William Morris’s daughter, May Morris, and the printer Emery Walker, in Hammersmith. He was introduced to Eric Gill in 1906 and worked with him for the rest of Gill’s life. In 1907, when Gill and his family moved to Ditchling, Cribb went with them, as Gill’s assistant Cribb’s career as a craftsman is testament to his innate abilities, to his loyalty to Gill and to the strength of Gill’ artistic practices and ideas, After Gill had formally established his own business cutting inscriptions in stone in 1905, he quickly built a reputation and had so much work that within two years he decided to take on an assistant. Emery Walker introduced him to Joseph (christened Herbert Joseph), the fourteen-year-old son of Herbert William Cribb, a graphic artist and map-maker working for Walker. Walker suggested that Gill take on Joseph, still a schoolboy, as his assistant. On 1 July 1906 Gill made a formal agreement to employ Joseph, starting at Gill’s workshop in Blacklion Lane, Hammersmith:

I AER Gill do hereby agree with Mr. H W Cribb to teach his son Herbert Cribb the trade, craft and business of a letter carver and draughtsman as practised by me and to allow him, at a time convenient to me, holidays of not less than three weeks in the year. Provided that he, Herbert Cribb, agrees, of his own free will and binds himself to learn the above craft and business for the period of one year from this date [18 June 1906] and that in consideration of the fact that no premium be required by me – no salary be expected until that term at least has expired … And provided that Herbert Cribb agrees and promises that he will, during the said term, loyally execute my lawful instructions … and will in all respects acquit himself faithfully and with diligence.

In 1908 Walker and Joseph’s father witnessed Joseph’s agreement to continue for a further five years, but now in the more formal role as Gill’s apprentice. Within a year Cribb was well established as an essential part of Gill’s workshop, shaping and preparing stone panels for inscriptions, and cutting inscriptions to Gill’s designs.

Although Gill’s business in London was flourishing, in 1907 he decided to move to Ditchling, ‘simply because London seemed an impossible place for children’. Along with Gill’s family, Cribb and the workshop came too: ‘I was able to shift the whole show, faithful apprentice and all, to Ditchling. Cribb was now sixteen and the move gave him an opportunity to follow his two hobbies, fishing and collecting beetles. Fishing remained a lifelong passion, and his collection of Sussex beetles was unparalleled and can now be seen in the Booth Museum. Brighton.

The move created a new life for both Gill and Cribb, bringing them into contact with rural life and crafts. Gill was inspired by the calm and beauty of Ditchling, and added wood-engraving and sculpture to his repertoire, and his letter-cutting developed a distinctive style which continues to be influential in the present century.

In Ditchling, Gill also became a prolific essayist, developing his own theories about artistic production and social equality. After Edward Johnston and Douglas (later Hilary) Pepler had moved to Ditchling, in 1912 and 1915 respectively. Gill was able to discuss and develop his theories further. When Gill was thinking about becoming a Roman Catholic, it was Cribb who accompanied him to Mass on 10 March 1912. After Gill and his wife were accepted into the Church in February 1913. Joseph followed them on 7 June, a week after he had completed his apprenticeship.

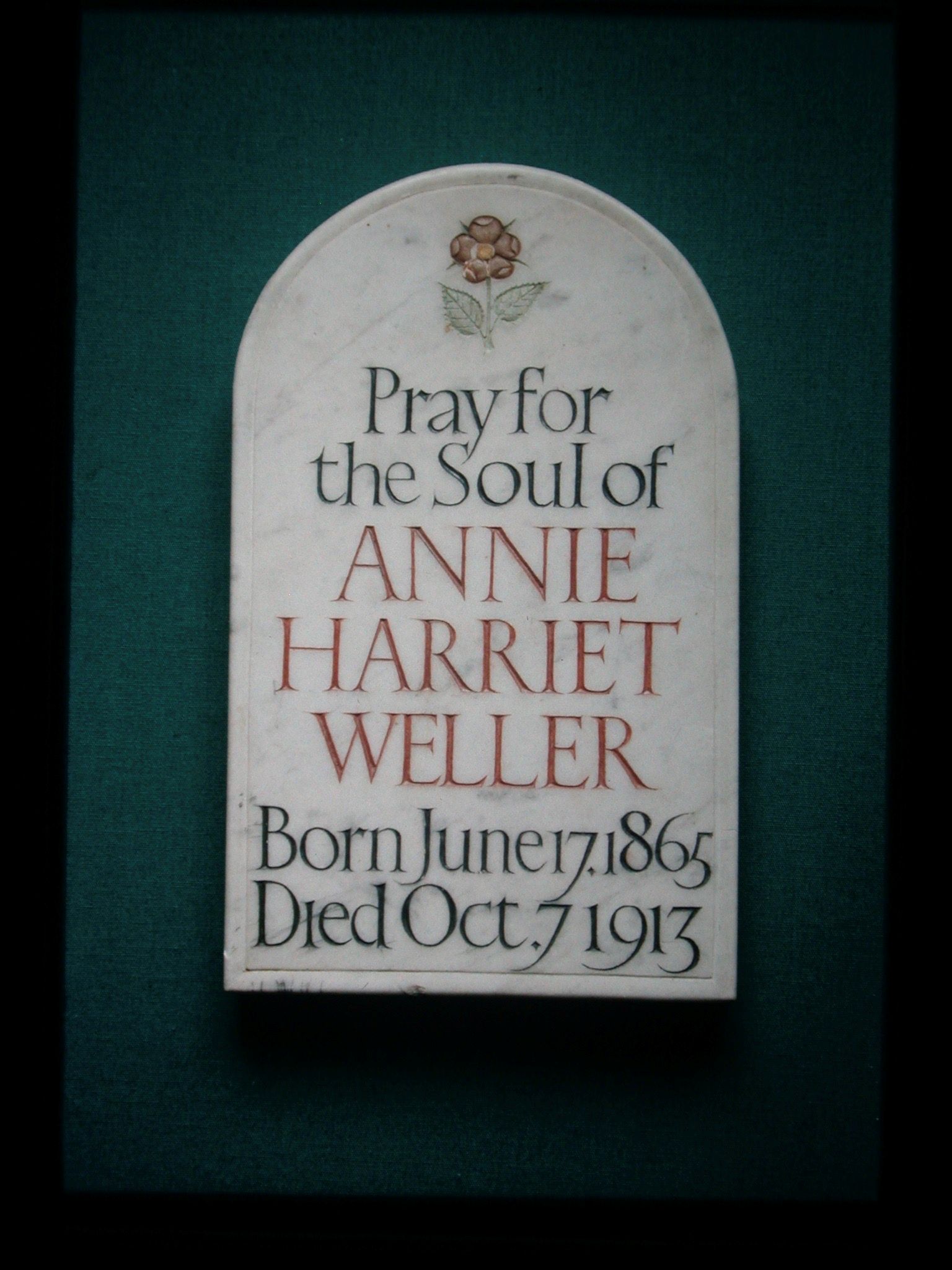

Gill’s busy life in Ditchling, with frequent visits to London to keep up with his many artistic and intellectual contacts, placed additional responsibilities on Cribb. After six years of training as assistant and then apprentice, Cribb had become an accomplished carver. He was now Gill’s most trusted associate, working on both inscriptions and sculpture and supervising the work of other assistants hired by Gill. Cribb’s workbooks from 1910-20 survive and show him working almost full time executing Gill’s inscriptional work, often carrying out the complete job on his own to Gill’s drawings. Cribb’s workbooks and Evan Gill’s catalogue of inscriptions show that Cribb worked on almost a third of the 300 inscriptions attributed to Eric Gill from 1910 until he left Ditchling in 1924.

When Jacob Epstein asked Gill to design the long inscription to go on the base of Oscar Wilde’s tomb. Gill sent Joseph with the drawing to Paris. Cribb’s workbook shows him spending 117 ½ hours working on the inscription during September and October 1912. The inscription on the front of the tomb is Wilde’s name and on the back is an account of Wilde’s life with a quotation from one of his poems, in all, consisting of about 750 letters. Cribb was therefore cutting the inscription at an average rate of one letter every ten minutes. His workbook also records that he was allowed two days of sightseeing; this included a visit with Epstein to the studio of the sculptor Auguste Rodin (1840-1917).

Cribb’s workbook documents his rapid development from apprentice letter cutter to skilled craftsman. He helped Gill with his major sculptures, shaping the stone, roughing out designs and polishing completed pieces. For example, he spent 44 hours, from March to July 1910 on Gill’s relief A Roland for an Oliver. In October 1910, a year after Gill had made his own first sculpture, Cribb was also encouraged by Gill to practice his own carving skills on a practice piece of a woman’s head. A few months later, Gill asked him to carve a marble tortoise. With the money he earned from this, Cribb was able to buy his own set of tools from Gill. As an apprentice Cribb had been paid sixpence an hour and after the end of his apprenticeship this went up to nine pence.

In 1913 Gill’s growing reputation as a sculptor and his recent conversion positioned him to secure the first major commission of his career, the Stations of the Cross for Westminster Cathedral. By now. Gill’s trust in Cribb’s skill and reliability enabled Cribb to work closely alongside Gill on the commission from the start. From December 1913 to February 1914, Cribb spent 135 hours working on the trial panel. The main work began in May, once the trial piece had been accepted. Over the next two years, Joseph put in a further 1,312 hours (164 working days). The general pattern of work suggests that Cribb was shaping the stone and roughing out the design, as his hours were mostly done before Gill’s, whose own workbook shows him concentrating on each piece. On Station no.1, the fourth to be completed. Cribb worked almost 300 hours, with his work time overlapping with Gill’s, clear evidence of their close collaboration, and of Gill’s need for assistants to help him complete his work. There is no way of knowing who carried out which particular aspects of the carving, as Cribb was able by this time to follow Gill’s drawings and instructions to the letter.

During the work on the Westminster Stations Cribb was also busy on many inscriptions. For example, he travelled to London to work on statue labels on Admiralty Arch and in Westminster, to carve the Pickering font and the Hornby memorial cross. In 1916, Gill was left to finish the Stations on his own, as Cribb left to fight in France. He returned to England, injured, in October 1916, but went back to France in May 1917. He spent the rest of his army service working as a draughtsman, firstly in connection with the laying out of railways, then later on the massive war grave cemeteries. One of Gill’s younger brothers, MacDonald, was commissioned to design the basic tombstone for the British war graves. Cribb was consulted about their design and drew up some of the regimental badges.

Cribb returned to Ditchling in 1919 to continue working with Gill. On his return, Cribb found a changing community, one much more focused around the Catholic faith. Father Vincent McNabb, the Dominican Prior of Hawkesyard Priory in Staffordshire was a regular visitor, and Desmond Chute, a young Catholic artist, had moved in with the Gill family. With them and Pepler, Gill had begun planning a religious community of craftsmen on Ditchling Common. Gill, his wife. Pepler and Chute became lay members of the Dominicans in May 1918, and in July of that year they met to start the process of setting up their new community. Cribb and his wife also joined the Dominicans and when the community was formally instituted as the Guild of St Joseph and St Dominic on 18 July 1920, he was one of its founding members with Gill, Pepler and Chute.

While the Guild developed, with new buildings and a daily routine of work and prayer, Cribb continued to assist Gill in his many inscriptional commissions, with much of the work now being for war memorials. These included the memorials for Ditchling village and the Victoria & Albert Museum during 1919, for South Harting, Angmering and West Wittering in Sussex and Betteshanger in Kent during 1920, and for the British Museum, Trumpington in Cambridgeshire and Dunmow in Essex during 1921. Cribb’s diary for his work on the Dunmow memorial reveals the extent of his expertise in letter cutting: it documents that he was cutting letters at the rate of 20 letters an hour. During 1921 he also began to secure his own commissions. This is an indication of Cribb’s own skill and reputation by this time, but perhaps also of Gill’s increasing workload. Cribb’s first independent commission seems to have been a war memorial panel for Northleach in Gloucestershire during 1921. His first large· scale commission, another war memorial, for Downside Abbey, followed soon after. This consisted of six panels of names, headed by coats of arms, with a large commemorative panel in Latin and a statue of the Crucifixion, flanked by the Virgin & St John. The style of the resulting work shows Gill’s influence, but it is distinctive enough to indicate Cribb’s in dependence as a sculptor, and as a letter-cutter with his own manner of working. During the 1920s Cribb exhibited his work, both religious and secular, with Gill at the Goupil Gallery in London, evidence that he had by this stage gained in confidence and developed his own style.

In 1921 Cribb’s brother Lawrence (known as Lawrie) started visiting Cribb in Ditchling. In June that year Cribb showed him how to paint carved letters, and by March 1922, Lawrie was able to work alongside Cribb on the Downside commission. In April. Lawrie joined Cribb to work on an inscription for Gill at Clifton College in Bristol and was now a key member of Gill’s workshop team in the Guild.

When Gill left the Guild and Ditchling on 13 August 1924, his intention was that Cribb should follow him to Wales and continue working as his chief assistant. However, Cribb chose to stay in Ditchling, though he continued to work closely with Gill. From late 1924 and into 1925, he carved the Stations for the Catholic Church of Our Lady & St Peter’s at Leatherhead in Surrey to Gill’s designs. Gill posted these to him from Wales. Cribb’s brother. Lawrie, assisted him in this work, but then moved to Wales to work directly with Gill. Lawrie quickly became Gill’s right-hand man in his new workshop. Soon after Lawrie had arrived at Capel-y-ffin, Gill wrote to Cribb that ‘Lawrie is well & I’m keeping him busy. I find him a bit slow – but he’s as good as real yellow gold‘. For the rest of Gill’s career, Lawrie was kept busy not only executing his inscriptions but also overseeing the work of Gill’s other assistants in the workshop. There were, however, many occasions when Gill sought the help of Joseph Cribb on important jobs, particularly when Gill needed to be able to rely on the work being done without close supervision. For example, in 1927, when Brighton Council asked Gill to make a plaque to mark the house where the politician George Canning had resided, Gill asked Joseph to do the job. Gill only provided a suggested layout for the inscription and design, so that it was Cribb who did the drawing for the inscription and executed the plaque.

Cribb continued to work in Ditchling, and his presence ensured the survival of the Guild. Cribb embraced Gill’s ideas on workshop practices, and conducted his working life according to those practices. He continued to work by hand, using no power tools to shape, carve and cut letters. His only concessions to the modern world were the telephone, from 1937, and electric lighting, from 1950. He charged for his work strictly on the basis of the time spent in executing it, and his main output consisted of church sculpture, inscriptions and tombstones.

Cribb’s career as a ‘sculptor, letter-cutter and carver lasted sixty years, the only break occurring during his service in France during the First World War. From the age of fourteen Cribb proved himself to have a natural talent for carving. When the design is by Gill it is impossible to distinguish between Gill’s and Cribb’s hands in inscriptions. Cribb’s own work as a sculptor and letter-cutter only became distinctive after his return from France, when he started to secure his own commissions and began to develop an independent approach to design. Like Gill, Cribb was much influenced by medieval sculpture. While Gill used this as a starting point for elaborating a very distinctive personal sculptural style (also drawing from Indian sculpture), Cribb stayed closer to the medieval, particularly the Italian and French Romanesque styles of that period.

From his first commissions in 1921 until his death in 1967 Cribb was always in work, and hundreds of examples of his work survive. During his career he designed and carved at least twenty sets of Stations of the Cross, following on from his execution of the Leatherhead Stations for Gill in 1924-5. His first set was commissioned by Fr Vincent McNabb for Hawkesyard Priory in 1928 and his most prestigious set was in 1956 for the new Roman Catholic Cathedral in Plymouth. His workshop was so busy that he took on two assistants, Noel Tabbenor in 1934, and Kenneth Eager in 1946, and he offered training to others, most notably, Gill’s nephew, John Skelton, from 1941 to 1942. Much of Cribb’s work is in churches throughout Britain, and he occasionally undertook secular work, such as on the former Argus building, the Anglo-Irish Bank, and the Fire Station, all in Brighton. He also carved designs by other local artists such as MacDonald Gill, Frank Brangwyn, Charles Knight and Louis Gannett.

Fittingly, after a career of over sixty years, Cribb died on his way to work at the Guild workshops on 6 November 1967. He is buried in Ditchling Churchyard. His grave is marked by a stone cut by his assistant Kenneth Eager.

Joe Cribb – 2007

Further Comments

Cribb’s devotion to the Guild extended beyond his craft to involvement with all the areas of community life of the Guild and the local community including offering his skills as a calligrapher, making greetings cards, organising St Dominic’s Day sports and acting as an Air Raid Warden in WW2. In so many ways, his life exemplified all that was good and profound about the Guild.