Table of Contents

Introduction

Arts and Crafts is a term often used, but difficult to pin down. It wasn’t a distinct style but an approach to design, working and living based on understanding the qualities of materials and the joy of craftsmanship. It is associated with styles as divergent as Pre-Raphaelite paintings, Art Nouveau architecture, neo-Shaker furniture, highly decorative wallpaper, and simple whitewashed walls. It is too, a term often associated with the Guild, but the relationship is problematic. The Ditchling Museum is pointedly called the Museum of Art + Craft to avoid invoking the term itself. In this article, I will attempt to give a brief history of the Movement, as it is often called, and highlight areas of connection and divergence with the thinking that underpinned the Guild

The Arts & Crafts Movement – brief history

The movement grew out of several related strands of thought during the mid-19th century. It was first and foremost a response to social changes initiated by the Industrial Revolution, which began in Britain and whose ill effects were first evident there. Industrialization moved large numbers of working-class labourers into cities that were ill-prepared to deal with an influx of newcomers, crowding them into miserable ramshackle housing and subjecting them to dangerous, harsh jobs with long hours and low pay. Cities likewise regularly became doused with pollution from a bevy of new factories. The Great Exhibition of 1851 showcased the products of Industrialisation and inadvertently caused many to question the entire process

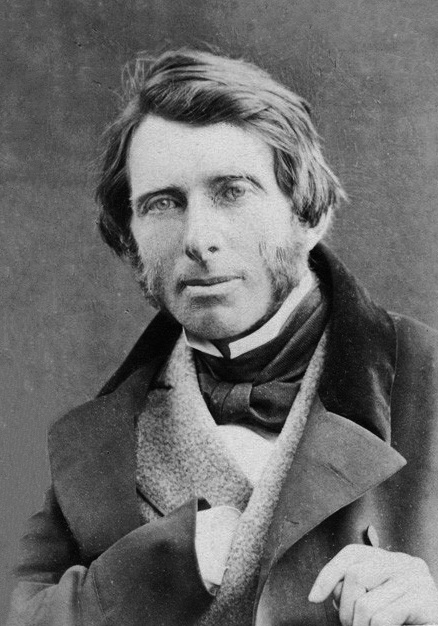

Chief among these was the art critic, John Ruskin (1819-1900). He wrote prolifically on the subject of social reform, arguing such arduous, monotonous working conditions were dehumanising and demoralising, offering little room for creative expression or autonomy. In his publication Unto this Last: Four Essays on the Principles of Political Economy, 1862, he described Britain’s industrial society as a destructive force that was driving labouring classes deeper into poverty and unhappiness. For Ruskin, the solution to such problems lay in the art of the Middle Ages, where high-quality products were made in small-scale Guilds and workshop spaces which trained workers to take real pride and ownership in the objects they designed and produced. He believed that creative labour, channelling both intellectual and physical abilities, was the healthy foundation for a truly fulfilling society, calling for business leaders to take responsibility for their workers by “shaping the market” with fewer, well-made products that were designed to last.

Ruskin too addressed the idea of Division of Labour, which was crucial to the idea of industrialisation. In The Stones of Venice, he wrote ‘We have much studied and much perfected, of late, the great civilized invention of the division of labour. Only we give it a false name. It is not truly speaking the labour that is divided, but the men – divided into segments of men – broken into small fragments and crumbs of life; so that all the little piece of intelligence that is left in a man is not enough to make a pin or a nail, but exhausts itself in making the point of a pin or the head of a nail’. Thus, he saw division of a labour as central to the dehumanising programme that was inherent in the industrial world.

These ideas were taken up by the architect, Augustus Pugin (1812 – 1852) and a young man attached to the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood called William Morris (1834 – 1896). In 1861, he founded the decorative arts firm Morris, Marshall, Faulkner & Co which specialised in decorative wallpaper. Morris’ firm grew throughout the 1860s and 1870s, especially as Morris garnered important interior design commissions, such as for St. James’s Palace (1866) and the Green Dining Room at the South Kensington (now Victoria & Albert) Museum (1866-68). It also expanded in terms of the range of items that it manufactured, including furniture, such as the famous “Morris chair,” textiles, and eventually stained-glass. In 1875, Morris bought out his partners and reorganized the firm as Morris & Co. Morris’ firm emphasized the use of handcraft as opposed to machine production, creating works of very high quality that Morris ultimately hoped would inspire cottage industries among the working classes and bring pleasure to their labours, thus creating a kind of democratic art. Those who adhered to this philosophy eventually became known as members of the Arts and Crafts Movement.

The ideas were applied to a whole range of creative activities such as furniture making, garden design, printing, architecture and stained-glass. In architecture for instance, a style developed which had at its heart five main principles: clarity of form, variety of local materials, asymmetry, construction within the local vernacular and traditional craftsmanship. Meanwhile, Arts and Crafts gardens were marked by a division of outdoor spaces into separate areas, almost rooms, each of which had their own character based on different planting schemes.

The movement also had a sharp political edge insofar as it opposed capitalism. It also saw the need for co-operation between craftsmen over such matters as premises and pooling of skills, and so revived the medieval idea of the craft guild. Ruskin himself was involved in an early attempt, later guilds that thrived included Arthur Mackmurdo’s Century Guild, and The Art Workers Guild. Crucially, in 1887, the more militant Arts & Crafts Exhibition Society, which gave the movement its name, was formed in London, with Walter Crane as its first president. It held its first exhibition there in November 1888 in the New Gallery. The aims were to “[ignore] the distinction between Fine and Decorative art” and to allow the “worker to earn the title of artist.” Dominated by the decorative arts, and bolstered by a strong selection of works by Morris & Co., the first two exhibitions were financial successes. Upon switching to a three-year cycle starting in 1893, the Society’s exhibitions served to keep the Arts & Crafts movement in the public eye and proved to be critical successes into the new century.

Meanwhile, in 1888, CR Ashbee had set up the Guild and School of Handicraft, which favoured a more rustic style than the increasingly eclectic styles that were emerging elsewhere. This Guild moved to the Cotswolds in 1902, but only survived until 1907. The Cotswolds were also notable for the Daneway Workshop partnership of Ernest Gimson, Sidney Barnsley and Ernest Barnsley. Several other prominent figures of the movement made their way alone; these included Philip Webb, Charles Voysey, W.R. Lethaby, and Norman Shaw.

Later in his life, Morris perceived the bitter irony of his success with the discriminating middle classes while his aims of bringing art to the working people had failed. He once said, ‘I spend my life ministering to the swinish luxury of the rich’.

Involvement of Gill

The London Arts and Crafts movement had come to be centred on Hammersmith, and this is where Eric Gill moved in 1905. Initially he was much taken with the circle of practitioners he found there (which included Morris’s daughter May and the printer Emile Walker) but soon his faith wavered. Like Morris, he saw that it was hard for craftsmen to sell for good prices except to dilettante markets, and that it was all too easy for mass producers to imitate and so debase the work of such craftsmen. He retained though, his basic interest in the original ideas of Ruskin, but felt that they had not been properly followed through. It was such ideas he would take with him when he left Hammersmith for Ditchling, including a profound distrust of industrialisation and a belief that art and life should not be separated but bound together by craftsmen making beautifully designed objects that would be both visually appealing and serve a purpose. Morris had advised, “have nothing in your houses that you do not know to be useful or believe to be beautiful”. Gill would have said useful and beautiful.