It is November in Sussex, … it is 6:00am. This is the time that the Guild members, in the early days, would have been walking over the fields from their houses to their small brick chapel for morning Office. With a hollow click the latch of the plank door, with its weathered grain and wooden pegging, opens and, stepping onto a threshold of scrubbed brick, you would breathe in the chapel’s distinctive smell, a mixture of whitewash, brick, books, leather from the kneelers and polish. Finding your place, the simple wooden benches scrape as they adjust to your weight. The air is still, damp and very cold, but then the candles are lit and the whitewashed walls glow, and dusty colour springs from the small statues of St Dominic and St Thomas Aquinas, from the red painted inscriptions on the carvings behind the altar and from the small bunches of wildflowers placed on a high windowsill or by one of the few carvings.

Morning Office begins: Lord open our lips … and we shall praise your name.

From David Jones and the Guild of St Joseph and St Dominic – an essay by Ewan Clayton

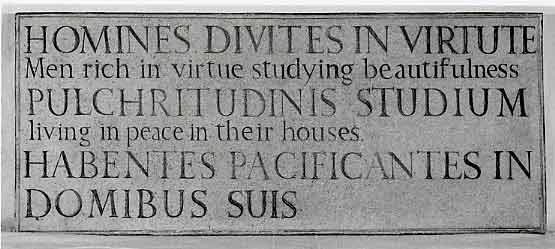

The Guild of St Joseph and St Dominic was a unique experiment in communal life, founded in the early twentieth century and located on Ditchling Common in rural Sussex. The story of the Guild began when Eric Gill, the controversial sculptor and letter cutter, came to Sussex in 1907 with his apprentice Joseph Cribb, soon to be followed two other associates from the Hammersmith Arts & Crafts world: the calligrapher Edward Johnston and social theorist, Hilary Pepler. In 1920, they founded the Guild of St. Joseph and St Dominic, this being a Roman Catholic community based on a medieval model. It was a community which united work, faith and domestic life centred on its workshops and chapel; its philosophy was encapsulated in what today might be called its mission statement, engraved on a stone plaque which is now in Cheltenham Museum.

This statement sets out the hope for a new Eden in which wealth was to be measured by virtue rather than money. Beauty would be the goal of production rather than output, and there was also a strong domestic element, characterised by peaceful existence. Also, it must be said, it was to be an Eden dominated by men – no woman would be admitted as a Guild member until 1972. Its philosophy drew strands from the Arts and Craft movement, from Catholicism and from the Distributist ideas of Arthur Penty, GK Chesterton and Hillaire Belloc. Its years of growth followed the Great War, when many young people had come to see modern life and industrial production as venal and dehumanising.

Soon the fame and membership of the Guild grew, more members joined, including the painter and poet David Jones, carpenter George Maxwell, and engraver Philip Hagreen. A key element of the community was the Saint Dominic’s Press, which was run by Hilary Pepler and enabled members to circulate their ideas to friends and supporters. The monthly journal it produced, ‘The Game‘, is still much sought after today.

With little notice, Eric Gill left Ditchling in 1924, leaving his apprentice Joseph Cribb to take over the stone carver’s workshop, but the Guild continued to flourish. It attracted many new members, notably the weaver Valentine KilBride and, in 1932 the brilliant silversmith Dunstan Pruden. Notwithstanding several upheavals, the affairs of the Guild eventually stabilised, and it continued for many years; the core of the group was to become Maxwell, KilBride, Pruden and Cribb who together totaled nearly 200 years of membership and service.

Later prominent members included artist and engraver Edgar Holloway who joined In 1950, stonemason Kenneth Eager, Jenny KilBride (the first female member) who took charge of the weaving workshop and calligrapher Ewan Clayton, grandson of Valentine KilBride. The Guild was finally wound up in 1989 and the workshops demolished.

Let me end this introduction as it began – with some reflections from Ewan Clayton about Guild life on Ditchling Common:

“Simplicity, gentleness, peacefulness, domesticity and a kind of unsensational holiness, which is not about being heroic but is about living in a place that you love and learning to respect its rhythms and its plants and its animals and to love them and to go through season after season and the cycles of family life and to celebrate them as a community, in an ordinary way, where your spirituality is an ordinary spirituality rather than an extreme one …

… and where it is a given, a normal part of life, that you make things with your hands.”

I hope you enjoy this site; I would be grateful to receive any comments, suggestions or new material.

John Price – jp@guildjosephdominic.org.uk

April 2024