Table of Contents

Introduction

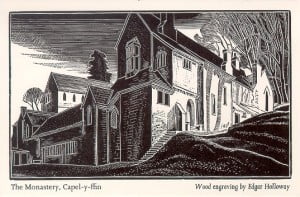

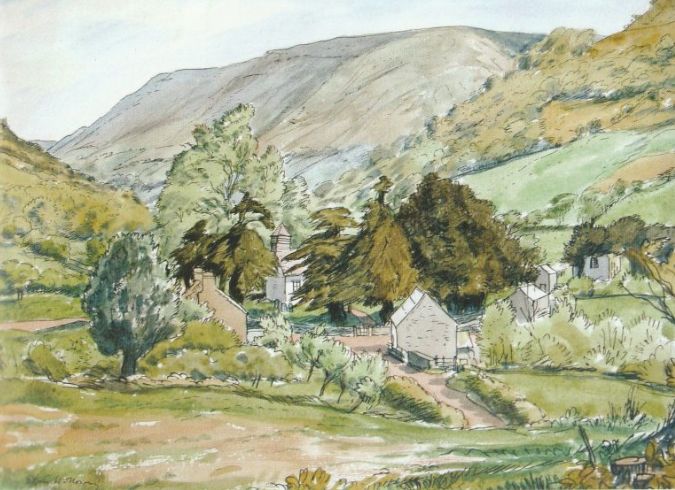

When Gill left the Guild, he moved to a mostly disused Anglican Monastery near Hay-on-Wye, on the edge of a hamlet called Capel-y-ffin. This property had a history every bit as extraordinary as that of the Guild itself. The hamlet located in the Vale of Ewyas, is the steep-sided and secluded valley of the River Honddu, in the Black Mountains of Wales, only accessible by a single track road which is the highest in Wales.

The Monastery itself had been built in the nineteenth century, and was arranged around a courtyard or ‘garth’. Three of the sides were two storied, and the outer part of these sides consist of a corridor. Nearly all rooms rooms face inwards, many of those on the upper floor being the monk’s cells. Near the Monastery are the ruins of what once was the Monastic Church.

The Monastery is an important part of the Guild story, being visited by many Guild members and associates over the years. I think of it as a kind of alter-ego to Ditchling, its wild setting contrasting with the Sussex Downs. Indeed, the former Archbishop of Canterbury, Rowan Williams who visited the Honddu Valley regularly, referred to it as what he called ‘a thin place’ where the distinction between the physical and incorporeal is slight. The Monastery is certainly worth visiting

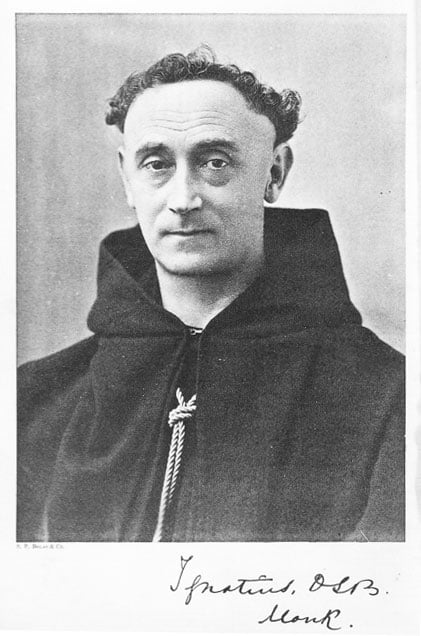

Father Ignatius and the early history

Joseph Leycester Lyne, known as Fr Ignatius (1837-1908), was a prominent figure in the Catholic Revival which swept the 19th century Church of England. As a young man he resolved to restore the monastic life lost at the Reformation and devoted the rest of his life to this aim. After various temporary homes elsewhere, notably in Norwich, he decided to relocated to the Welsh Borders, near Hay on Wye. Ignatius had originally hoped to acquire the remains of the medieval Augustinian house at Llanthony but when this proved to be impossible, he brought his fledgling community to Capel-y-ffin in 1870 three miles down the valley. This new settlement was variously known as Llanthony Abbey, Llanthony Tertia (following on from the nearby original Llanthony Priory, and its Gloucestershire offshoot Llanthony Secunda), and New Llanthony Abbey. Architect Charles Buckeridge was instructed to design a replica of its 212-foot-long priory church, but only the choir was built, together with living quarters which would, if completed, have been rather more than double their present size. These would have included a permanent convent for the associated community of enclosed nuns; from 1881 its members – never more than five – occupied a temporary single-storey building on what is now a level lawn alongside the ruined monastic choir.

In addition to the monks, the monastic household also included a few boys, usually from poor or broken homes. In return for board, lodging and occasional lessons they assisted as singers and servers with the ornate and elaborate services in the Abbey Church.

Fr Ignatius himself varied his life between that of the cloistered monk and the peripatetic friar, frequently being absent from the monastery on preaching tours. When he was there, his rule was odd to say the least. He insisted on strict observance of the monastic rule on the part of the monks while observing very little of it himself; when faced with a rebellion about this anomaly, he expelled all his monks. It is also recorded that he would punish the offence of a monk speaking to a non-monk by forcing the miscreant to wear an article of secular clothing for three days; one brother complied by wearing a top hat. Given the flawed leadership, turnover among the monks was understandably high and when Ignatius died on 16 October 1908, there were only three left to carry on. Ignatius himself was buried twelve feet beneath the floor of his Abbey church. After struggling for a year to keep the Monastery going, the surviving monks were absorbed by an Anglican Monastery at Caldey whose community was younger and more vigorous, as well as being closer to the Anglo-Catholic mainstream. Fiona McCarthy described the story as ‘a tale of hopelessly misdirected fervour’, an understandable sentiment, although others, notably The Fr Ignatius Memorial Trust, take a more positive view of his life and work.

In March 1913 most of the Caldey community were received into the Roman Catholic Church and so ownership of the Monastery effectively moved to the Benedictine Order. In due course, the Caldey Community relocated to Prinknash in Gloucestershire, following which the buildings at Capel-y-ffin were sporadically occupied by Benedictine Monks on retreat and occasionally others.

Gill’s Occupancy – 1924 – 1928

Following the acrimonious split with the Guild, Eric and Mary Gill leased part of the Monastery and arrived at Capel to live with two of their three daughters (Betty and Joan) on 13 August 1924. They were accompanied by Philip and Aileen Hagreen and the Brennan family who were farm labourers from Ditchling. Already in residence at the Monastery two monks from Caldey, Father Joseph Woodford and Brother Raphael Davies. Also present were a young man contemplating his future, René Hague, and an authority on Eastern rites and friend of Gill’s, Donald Attwater and his wife. The property had not been fully occupied for many years and was semi-derelict, basic services were at a minimum and the church built by Fr Ignatius was deteriorating badly.

Gill had hoped that Joseph Cribb would join him in Wales, but Cribb turned this down. Instead, Gill got the next best person – Cribb’s brother Lawrence, himself a brilliant letter-carver, was attracted by the Welsh mountains and came to Capel – he was to be Gill’s main assistant for the rest of Gill’s life. His work can be seen on two gravestones in the local churchyard along with one example of Gill’s.

Gill however was not daunted. He created a chapel in the loft of the north wing and daily mass was soon instituted. Gill’s work too received a boost. He quickly set up a workshop and his time in Wales produced many sculptures. It is also notable as the time he designed several of the fonts that became famous, most notably, Gills Sans. He still had aspirations to create a guild-like organisation at Capel and drafted a constitution for the agreement of Jones, Hagreen and another visitor, artist-monk Dom Theodore Bailey. It was universally rejected and then forgotten.

Philip Hagreen and his wife did not settle at all, finding the damp climate and cold building not conducive to good health. They left and relocated to France, living for some years in and near the pilgrimage town of Lourdes in the Pyrenees, before Hagreen rejoined the Guild in 1930.

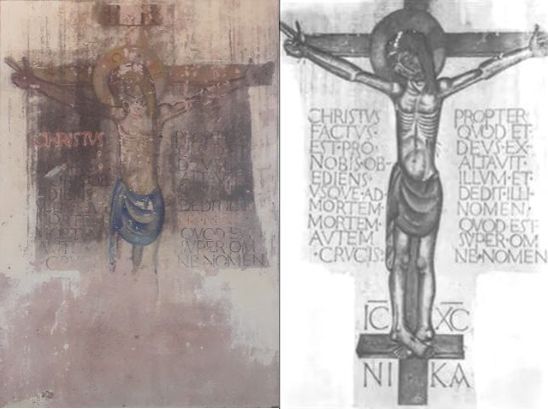

Another Guild character who was to spend much time at Capel was David Jones. He produced many paintings of the landscape which critics feel show his artistic style developing to maturity as well as giving him a vision of his own Welsh nationality. It was during this time that his engagement to Gill’s daughter Petra was ended, an event that caused him great sadness. Petra then became engaged and was soon married to another Gill acolyte, Denis Tegetmeier. He left his mark on the building in the shape of a painting of the Crucifixion on the kitchen wall, then the chapel (far left, as it is now, left, as it was). The lettering is of the Christus factus.

There was also romantic developments for the other Gill daughters. Betty married David Pepler in 1927 and went to live in Sussex, in the Guild cottage, St Rose, trying to make a living by farming the land of Fragbarrow Farm; it was felt that David’s poor health would profit from the outdoor life. Also, René Hague found himself much taken with the youngest girl, Joan; they were to marry in 1930.

For Gill though, living in Capel was no more than a transitory arrangement. His clientèle was in London and that is where he found himself spending most of his time and he went so far as to acquire a London property. In 1928, he called time on the remote-living experiment and moved his wagon on. His next home was to last for the remaining twelve years of his life; it was a complex of farm dwellings called Pigotts, not far from High Wycombe in Buckinghamshire. Again, he had his extended family with him and again the various buildings were arranged around a courtyard, but this time the location gave him a balance of country living and nearness to London.

After 1928

When Gill left Capel in 1928, he and Mary did not abandon all interest in the Monastery. On the contrary, when Mary received a legacy from her mother in 1931, she used this to purchase the entire property from the Benedictine Order. When their daughter, Betty, lost her husband David (Hilary Pepler’s son) to cancer in 1934, she and her five children moved there from Sussex and opened a school in the building. In 1938, she remarried, this time to Harley Williams and she had three further children, meaning that as well as a school, the monastery was home to a large family. The school closed at the start of WW2 and after that the surplus accommodation was used as a Guest House.

One minor activity was to host Hilary Pepler and his daughter Susan, who ran a mime class in 1933. During this interlude, Susan fell in love with attendee David Faulkner, and they subsequently married. Another Pepler daughter, Jane, married Laurie’s Cribb’s son Felix.

In the late 1930s, when Gill was living at Pigotts, he conducted an affair with his model and family servant, Daisy Monica Hawkins. For once, Gill’s wife objected and so it was arranged for Daisy Monica to move to Capel where she lived for some years, helping with the business. In 1943, after Gill’s death, a struggling young artist called Edgar Holloway visited the Monastery for a period of reflection. There was an immediate attraction between Holloway and Daisy Monica, and they were married six weeks later in Abergavenny and spent most of the following years helping to run the guest house. This came to an end in 1949 when Edgar accepted an invitation from Philip Hagreen to join the Guild of St Joseph and St Dominic, where he stayed to the end – he was to be its last chairman. He had three children with Daisy Monica, who died in 1979. Holloway continued to visit the Black Mountains for the rest of his life. Indeed, it was here that he rediscovered his appetite for painting watercolours in the 1970s.

Yet another romance bloomed when an RAF Warrant Officer called Wilfred Davies visited the Monastery and fell in love with Betty’s eldest daughter of her first marriage, Helen; they married in 1951. In 1956 Betty died and for a while the guest house was carried on by her daughter Jane and Laurie Cribb’s son Felix who had recently married. After they left, a non-family housekeeper was appointed and then, in 1961, Mary Gill herself died, leaving the now run-down monastery to Wilfred and Helen. Wilfred had now retired from the RAF and the couple decided to move to the monastery to restore its fortunes, assisted by his brother-in-law Paul Pepler (Helen’s brother) and his wife, who also moved back to Capel. Over the next few years, Wilfred and Paul conducted a systematic programme of repair and improvement. He also found time to cultivate the former monastic kitchen garden, brew industrial quantities of beer, and to play the ukulele at family gatherings. Both couples had large families, so the dark corridors again reverberated to the sound of children’s voices, strangely, all descended from Eric Gil and Hilary Pepler. During the two decades that they lived there, Monastery hospitality was greatly appreciated by members of their large extended family, friends of their children, an assortment of neighbours, visitors to the holiday flats in the former west cloister, as well as other sundry individuals, many connected with Gill or Father Ignatius.

One of the guests in this period was former Guild Postulant and controversial friar, Fr Brocard Sewell who stayed for over a year around 1970 after he had made himself persona non grata with the Carmelite Order by opposing the Papal Encyclical, Humanae Vitae. Sewell was also involved in the setting up of the Fr Ignatius Memorial Trust. Wilfred Davies was secretary of this venture and organised the clearing of all the accumulated rubble and fallen masonry from the ruined abbey church. He also instituted the annual pilgrimage to the site, which began with the abbey church centenary in 1972, and continues to this day.

Wilfred and Helen Davies left the Monastery in 1985 when their family had grown up and moved on, selling it to the present owners (the Knill family) who still run it as self-catering holiday accommodation (offering three flats) as well as a family home. Sadly, their time at the Monastery seems to be coming to a conclusion. As of July 2023, the property is on the market.

There remains a Gill and Pepler family link in that the nearest property (The Grange) was the home of Betty Gill and David Pepler’s daughter, Mary Griffiths (née Williams), who ran a sizable pony-trekking business, which is now operated by her daughter, Jessica, assisted by her own daughters.

The Llanthony Apparitions

Moving back in time, to 30 August 1880, strange events were reported at the Monastery. The focal point of the abbey church was the high altar with its lofty reredos and magnificent tabernacle reserved for the Blessed Sacrament as a ‘shrine of perpetual adoration’. That morning, 20-year-old Brother Dunstan was kneeling at a prie-dieu in the centre of the church, taking his turn at the daily ‘watch’, when he saw the monstrance containing the Host appear on the altar in front of the tabernacle door. Later the same morning, Janet Owens (an associate sister) had the same experience, but thought the Sacrament ‘had been left out for some reason’.

In the evening, the four ‘monastery boys’ were playing in the meadow below the building when they were startled to see a female figure apparently gliding across the surface of the field. They identified the figure as the Blessed Virgin Mary, and the apparition was seen on three further occasions over the following two weeks – on the final day, by Fr Ignatius himself, who had not been present on the earlier ones. The figure then appeared to dematerialise into a bush on the far side of the field.

Devotion to ‘Our Lady of Llanthony’ quickly took root, and leaves from the bush into which the vision had disappeared were believed to have miraculous properties and were taken away by pilgrims. The date of the first apparition, 30 August, was chosen as the festival of the apparitions, when the abbey church would be crowded with pilgrims from far and wide, many of them having walked the eleven miles from Llanfihangel Crucorney station or over the mountain from Hay. The day ended after Vespers with a procession to the site of the holy bush; eventually a commemorative statue was erected on the Monastery forecourt.

During Gill’s occupancy, the statue was removed to All Saints’ in Hereford (Gill had little interest in other people’s devotions), where it remained until the late 1960s, when it was returned to the Monastery forecourt. Meanwhile, a tiny piece of land, near the site of the holy bush, was acquired by Hilda and Irene Ewens, daughters of Fr Ignatius’s sister Harriet, and a wooden Calvary installed; a congregation of fifteen hundred assembled in the adjacent field for its dedication on 30 August 1936. The apparitions are still commemorated by an annual ecumenical pilgrimage.

Film

Capel-y-ffin marriages

While developing this article on the Capel-y-ffin monastery, I was stuck by the number of romances that have taken root is this atmospheric location. Here is a list of ones connected with the Guild and its families:

- Strangely, this list starts with a break-up – David Jones and Gill’s second daughter, Petra Gill realised that their engagement could not progress. Petra then became engaged to and soon married another Gill acolyte, Denis Tegetmeier, who she had known from Ditchling.

- Gill’s eldest daughter Betty had married Pepler’s son David in 1928 at Brecon, (at the same ceremony Laurie Cribb married Teslin O’Donnel) and moved back to Sussex. David sadly died 1934 and Betty then moved to Capel and in 1938 she married again, this time to Harley Williams, a local psychiatric nurse. She had five children with David Pepler, three with Harley Williams.

- Rene Hague, staying at the Monastery when Gill arrived, was attracted to his youngest daughter Joan and they married in 1930.

- In 1933 Pepler’s eldest daughter Susan spent a short time delivering a mime class with her father and met and fell in love with attendee David Faulkner whom she was to marry.

- In the late 1930s, Mary Gill persuaded Daisy Monica Hawkins to move from Pigotts to Capel to take her away from Gill who was greatly attracted to her. When the struggling artist, Edgar Holloway arrived at Capel in 1943, looking for peace and respite, he met Daisy Monica and they fell instantly in love and were soon married.

- One of Susan and David’s daughters, Jane, married Laurie’s Cribb’s son Felix around 1955. They then ran the Monastery for a short period.

- RAF Warrant Officer Wilfred Davies visited the Monastery in the late 1940s and fell for Betty’s eldest daughter, Helen (whose father was Hilary’s son, David); they married in 1951 and were to play a great part in the history of the Monastery when they moved there in 1961, in some sense bringing joy to a troubled location.

- Paul Pepler, (Helen’s brother and Hilary Pepler and Eric Gill’s grandson) and his wife also lived at the Monastery for many years, working with Wilfred and Helen Davies to restore its fortunes.

Further information

Books

- New Llanthony Abbey – Hugh Allen – highly recommended; written with great style, a sharp eye for detail and a lot of dry humour. The astonishing level of research lays bare the foibles of humanity without ever failing to show due respect for the many maverick personalities who occupied this singular building. Satisfies even the most curious reader (i.e., me).

- Try the Wilderness First: Eric Gill and David Jones at Capel-y-ffin – Jonathan Miles

Links

- David Jones and Capel-y-ffin – article about a recent exhibition in Brecon

- The Father Ignatius Memorial Trust

- The self-catering accommodation offered today – wonderful place to stay for a few days

- Travel article from 2006 – from the Guardian

- Further travel article, based on a BBC Secret Wales feature

- Walking from Partrishow to Capel y ffin – Trevor Fishlock – great video

- More information – from website about the Cistercian Way

- Wikipedia article on Fr Ignatius

- Wikipedia article on Llantony

- Grange Trekking