- Born 1890, died 1957

- Guild member 1921-1957

- Wheelwright, builder, carpenter, loom-maker

Table of Contents

Life

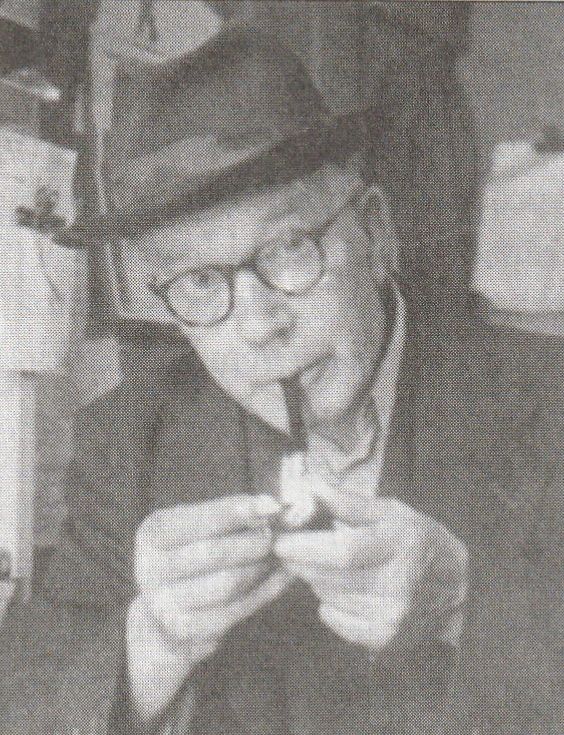

George Maxwell joined the Guild in the very early days, but was a different kind of member to the refugees from Hammersmith and the artistic circles of London. Maxwell had been employed in Birmingham during WW1 making propeller blades and later went on to work as a carpenter and wheelwright. He was a trade unionist, a devout catholic and committed distributist and a self-taught expert on St Thomas Aquinas. You might say, a working class intellectual. Gill was delighted with his new recruit; he described him as “a very great godsend, a dear man of beautiful and intelligent humility. He also approved of Maxwell’s wife, Cissie “also the right kind of Christian women – no intellectual high-browism about her” – a comment that says more about Gill than anyone else.

Having arrived at Ditchling, Maxwell devoted much of his life to the Guild. In the initial phase he was put to work on the various building projects, especially the St Rose and St Catherine cottages and his own home, Ferrers. As for many of the Guildsmen, the Catholic Church was to prove a major client and many Sussex churches were furnished from his workshop. he was assisted for many years by Cissie’s brother, Philip Baker, who joined the Guild in 1932 having become a postulant in 1921; he left the Guild when war broke out 1939 and returned to Birmingham, not to return, although he continued to work as a carpenter until retirement.

The Maxwells had five children, Winifred, Teresa, Vincent, Stephen and John. After the eldest boy, Vincent, entered the priesthood George had expected Stephen to join him at the Guild. However, Stephen enlisted at the WW2 at the age of only 16, causing George great upset as he knew well the dangers involved. Stephen survived until June 1944 when he was killed in Italy, near Monte Casino. The youngest son, John, then joined George in the workshop, something he was initially reluctant to do as he had hopes of becoming a farmer.

After the war, the workshop had to change direction. Demand for traditional furniture had fallen, but there was an upsurge in home weaving which greatly increased the demand for looms. This was accompanied by a falling of the supply from Sweden which had previously supplied much of the market. The workshop rose to the challenge, providing a bespoke service and at one time employing four assistants as well as George and John Maxwell. In addition to the traditional looms, they also developed folding looms and table looms for home operation where space was at a premium. Maxwell looms quickly established a reputation which survives to this day.

Maxwell was rigidly opposed to power driven machinery. He only used two small manual lathes and light was provided by paraffin lamps. When electricity arrived in 1953, its use was limited to one light bulb and a kettle. As George entered his sixties, his health deteriorated and he did less hands-on work, concentrating on administration and design. His accounts filing system was idiosyncratic. Paid invoices were pushed into a spike, and when the spike was full to capacity, the end was turned over to make a hook and then hung from another hook inserted in the ceiling of his office; and there it would remain. He died suddenly from a heart attack in 1957, aged 67.

The workshop was taken over by John Maxwell, but he found that the loom boom was over and work was scarce. At last however, powered machinery was introduced and he concentrated on furniture, always working to the high standards George has established. Failing health and lack of work combined to lead him to early retirement in 1973. His retirement was not long-lived however, he died on 1 November 1984, aged only 56.

George’s widow, Cissie, she of the lack of ‘intellectual high-browism’, in fact a lovely lady, lived a long life, revered by her friends and family, dying in 1978, aged 87.

George Maxwell has a slightly dour reputation and he was certainly not a frivolous man. His sincerity and integrity however were beyond question and there are many stories about how much Guild members like Philip Hagreen, Valentine KilBride and Hilary Pepler valued his friendship. Also, my father remembered well how George would make time to play ludo with him every day when Dad visited the Maxwells for a few weeks around 1935.

Work

It is something of a regret to all concerned that the location of relatively little of George Maxwell’s work is known today. In particular, I have not been able to identify any of the church furniture made by his workshop before World War 2. Here however, are some surviving photos of his other work:

Writing

Maxwell wrote many polemical articles and essays in his life, always advancing the causes of Distributism and the Catholic faith. In the first example, published in 1944, he tackles a subject close to modern hearts – refuge and recycling. He proposes that the careful use and disposal of waste is an important part of society, one that is respected in agricultural circles not neglected in the urban environment. The value of recycling and the environmental damage cause by reckless disposal is a lesson we have had to relearn. The second essay considers the nature of work. In both, Maxwell’s intelligence and concern shine through.

Obituary by Valentine KilBride